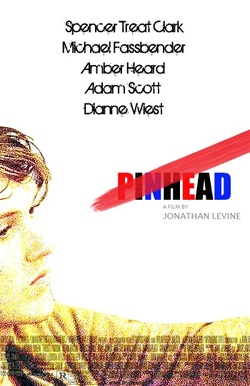

PINHEAD (Douglas Reese of USA)

Written and Directed by Jonathan Levine

Produced by Olivier Delbosc and Jonathan Levine

Music by Robert Earl Keen

Editing by Josh Noyes

Cinematography by Seamus Tierney

Main Cast:

Spencer Treat Clark … Ethan Elok

Michael Fassbender … Coach James Christian

Amber Heard … Kelsey Elok

Jeremiah Hall … Matthew Madison

Jaquelyn Xavier … Leah Weston

Adam Scott … Roger Elok

Dianne Wiest … Sharon Elok

Tagline: "When it comes to wrestling yourself… the victory seems further from reach.”

Plot: Graduation is just days away and this is his final wrestling meeting with Coach Christian and the boys. They all spend the final day competing in playful matches and Ethan Elok continues to toss and pin his way into pin after pin. Even outside of the competitions, he’s got to remain on top. Ethan is still overcoming the shock of turning eighteen, and his relationships with his best friend Matthew and his gal pal Leah have only spiraled out of control; Matthew finding company with a group of delinquents and Leah no longer interested in the occasional screw. After walking to that podium and accepting that diploma - school no longer a daily activity – Ethan dives into a world of emptiness. Nothing seems to be going on around him, and days spent at home are still as absent from his mother Sharon as they were during schooling hours.

But in this time – these days that pass by slowly – Ethan begins to collect visions involving himself. You can see in his eyes the desperation and the confusion concerning the direction of his life; and you can tell just by the way he speaks to his burnt-out older sister Kelsey that his emotions are slowly draining out of him. Between him and his mother, though, he feels like a reconnection with the deadbeat father he hasn’t seen in over a decade (save for the year’s wrestling competition he just so happened to show up to) may be the key to piecing together a solace to his complicated emotions.

In the wake of this upcoming event (an expensive dinner ultimately arranged by the father himself, Roger – who can’t normally afford such an occasion), Ethan alongside his mother and sister engage in an exhilarating conversation with the man that abandoned them all. All three react in different ways to the family history, but they all wrestle with their feelings while Roger still finds himself incapable of being the better person he wants to be. This moment surely becomes what Ethan was hoping for. Late the night of the dinner, returning home, two separate emotional talks between both sister Kelsey and mother Sharon opens his eyes to what he wants to do with his life. And just like that, he packs his things and walks out of the house, stealing Sharon’s keys on the way. Shadows no longer swallow him, but dance along with him as he passes each streetlight.

Press Section: Upon announcement of the film “Pinhead”, almost nobody felt it would add up to anything other than a sports drama that would be forgotten months after its theatrical release. However, Focus Features wasn’t being dumb when they backed the film up completely and allowed Jonathan Levine to put together a film of such immaculate naturalism and somber beauty. “Pinhead”is a sports drama – and a wonderful one, at that – but it’s not a film about who’s going to win a big competition or how good the protagonist is at the sport. It’s a film in which a boy spends years of his life projecting his frustrations through his physical wrestling skills and, ultimately, forced into finding a solution mentally in order to begin what he is to ultimately become. An adult.

Director Jonathan Levine brilliantly constructs various human themes under auteur allusions to form a tapestry expressing the universal coming-of-age story in a wonderfully magical way. Throughout the film - as the authenticity of the story is told through painful silences and bruising dialogue between characters – director Levine manages to subtly bring together metaphoric parallels between the main character of Ethan and of a superhero. From his name to the blue uniform he wears while wrestling on the mats, the character of Ethan is a frustrated person who fights the negative with his alter-ego (fellow jocks and friends in school have given him the nickname “Pinhead”). Although this isn’t about saving the world as much as his own demons, Levine makes it so that the character is portrayed as a symbolic (and perhaps director-personal) hero for those who can relate.

For the role of Ethan Elok, Levine searched out an actor who was fragile enough to show vulnerability, yet daring enough to bulk up to the challenge of showing Ethan’s aggressive flaws. For the part, Levine chose Spencer Treat Clark, who gives a scorching performance that resonates deeply. Whether it be the way his thoughts are projected through his eyes (after the first act, when his character is no longer in school, his performance mostly consists of an eerie silence in which he must emote through body language to keep the audience’s sympathy) or through the way he creates animalistic pathos during the wrestling sequences that verge on disturbing. It’s a brilliant, breakthrough performance that instantly creates a connection between viewer and character.

The rest of the cast is composed of a variety of terrific and natural actors and actresses who bring great depth to their supporting parts. The film is sternly shown from the eyes of Ethan, giving the supporting performers the task of making characters that only appear every so often in the film fully developed and functional at consistent wavelengths. Perhaps the largest of the supporting players is the role of Coach James Christian - played brilliantly by Michael Fassbender. The kind of stock character that is normally played to overtly hyper levels is given a fairly realistic treatment by Fassbender, who is unafraid of keeping his character’s vulnerability present in his actions even while he projects a fierceness and power over the boys on his team. There are two notably strong moments in Fassbender’s performance that makes him a strong candidate for a Best Supporting Actor nomination.

There’s a scene near the beginning of the film where Coach Christian expresses how much he is proud and respectful toward his players. It’s a monologue that could have easily fallen to melodramatic cheesiness, but Fassbender makes it so that it rubs off as painfully raw and heartbreaking as possible. He doesn’t shed a tear, but you can feel the sincerity in his voice. He really cares. It’s not until later in the film (during the actor’s second standout moment) that this speech takes on a stronger relevance. There’s a simple moment between Ethan and Coach Christian (which occurs at the end of the second act during a flashback to the competition that Ethan’s father showed up to) in which, after Ethan’s uniform rips during a match exposing his genitals to everyone in attendance, the coach chases the boy down to the locker room and embraces the shattered young adult. Levine makes the perfect judgment as director to linger on this shot by focusing on Fassbender’s face, his chin pressed against Ethan’s head as his eyes become viciously glassy as if to share the boy’s embarrassment and humiliation. It’s one of the film’s first moments of pure connection between Ethan and another person.

In a supporting role that goes totally against what has ever come from her before, Amber Heard sheds away all of her sex appeal for a performance that verges on a quiet tour-de-force. With dark brown hair, piercings, and eyes that look to be baked completely from her skull – Heard is a revelation in her role as Ethan’s older sister Kelsey. Heard only has a total of two big scenes in the entire film (as well as several little ones sprinkled here and there), but she sells the hell out of screentime by showcasing her commanding presence and her blissful naturalism. In her first scene, a conversation between her and Ethan on a couch following his graduation (and her return from a rehab center), we get a heartfelt exchange of words in which, while obviously tripping on some kind of drug, Kelsey expresses how she is truly happy for her little brother. “You’re nowhere like me. You’re out there somewhere. You’re not a loser.” This delivery beautifully contradicts what she says during a later moment in the film following the disastrous dinner with their father. Outside the restaurant, Ethan (who in the first scene involving Kelsey expressed his disgust with her smoking habit) begs for a cigarette “just to see if it does what you say it does!” This plea from him makes his sister slightly breakdown, as Heard delivers a scene of pure magnetic ferocity. Obviously holding back from crying hysterically by trying to project strength in her voice – she screams at her brother, letting it all flow out. “You’re dead, just like me, motherfucker. Don’t try to act like you’re not gone, too…” and her rant flows out with hostile rawness before closing up in a beautifully touching moment where they both share a laugh. There’s a serene understanding between Clark and Heard in their performances that makes them feel undoubtedly like siblings. That lifelong relationship – that bond- can be felt.

With Adam Scott and Dianne Wiest, who play the roles of father Roger and mother Sharon, respectively – Levine pulls off a bittersweet void of haunted souls by giving these two performers ample honesty to their roles as they make us believe that they were once an oddball couple (Sharon being decades older than Roger) when they conceived both of their children. It was obviously Roger who called off their romance, and he doesn’t seem to really regret it. He’s quite naïve, like a child, in the climactic dinner scene as he can’t seem to read the signals that Sharon still might have feelings for him. Both Scott and Wiest make this long-lost connection singe through the looks and words they speak to one another. The dinner scene is a master-class of subtly between the two – Scott looking rugged and shaggy in a faux tuxedo that is obviously too big for him, while Wiest lights up with a smile over his lame attempt of looking higher class.

Scott plays humorously with his character, but never makes Roger a caricature. He’s a crappy father and a dishonest person – but there’s a glimmer of love in him that seems to be lurking under the shell. The dinner scene almost feels surreal with Scott’s darkly humorous performance compared to the somberness the rest of the film possesses… but it never feels out-of-place as it slowly escalates to a compelling confrontation between father and son. The fire in Scott’s voice in that argument surprises and sends chills up the spine.

Another fantastically real moment in the film is a scene toward the end of the film involving Sharon showing Ethan a picture of her and his father from back in the day. Levine makes the terrific decision to never show the picture but, instead, has the camera lingering outside of the dining room for one long, uncut five-minute take. The audience peers directly into a very intimate moment between the two from a distance – never interrupting the beautiful moment between the two.

In smaller roles as relationships slipping away, unknown low-budget indie actors Jaquelyn Xavier and Jeremiah Hall bring memorable work to their very small parts. After the first act, they slowly fade from the film – but they perfectly capture the innocence and peculiarities of becoming an adult and realizing their lives may be going in a terrible direction. After having sex with Ethan at a senior party, Leah (Xavier) expresses how much she thinks she’s in love with another man; one who Ethan becomes either jealous or weary of (something else Levine beautifully leaves ambiguous.) There’s a final scene with former best friend and fellow wrestler Matthew (Hall) that blisters with hurt, in which both friends exchange a solemn look at one another. This following their previous scene together in which Matthew “can’t understand you anymore. You used to be a beast. You seem to be losing your claws, man. What’s happening to you?”

Overall, by breathing such liveliness into every character, the ensemble perfects their parts with flesh and blood – all feeling as human as can be. Director Levine amazingly avoids becoming episodic with the film in the way he weaves the many moments together with the use of brilliant film editing that never feels the need to play things out in typical linear motion and cinematography that feels almost French New Wave in its color palettes and use of color for symbolism. For example, the film opens up with the final wrestling meeting as Ethan attacks fellow mates - but the scene is intercut with Ethan in the locker room afterward as he strips from his uniform and takes a shower. Back and forth. We are first introduced to Pinhead – but we are going to get to know the naked truth about Ethan Elok behind that suit.

We experience a first act of the film dedicated to his graduation and the last moments with classmates and friends (Levine makes the wise decision of portraying the senior party in a bland, rather than typical John Hughes-cinematic fashion) and then the second act as we get to understand the true Ethan free of social influence (there’s a wonderful scene where he watches Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru on the television and can’t look away from it) and then leading up to the eventual dinner with the broken family (a nearly fifteen-minute long sequence that slowly boils to fury) that is preluded with the lengthy flashback to the ghostly piece of the Pinhead’s history. It makes sense, then, why Levine decided to end the film on that final shot. After packing up his things and stealing his mother’s car, Ethan drives away as passing shadows cast from the streetlights swipe over his face. The rich colors of his blue wrestling uniform and the bright reds of the gymnasium and locker room are no longer there. Neither are the greys of his mother’s home, or the uncomfortable vomit green of the restaurant. Only a warm and inviting yellow glow. Victorious.

Awards Consideration

Best Picture

Best Director – Jonathan Levine

Best Original Screenplay

Best Actor – Spencer Treat Clark

Best Supporting Actor – Michael Fassbender

Best Supporting Actor – Adam Scott

Best Supporting Actress – Amber Heard

Best Supporting Actress – Dianne Wiest

Produced by Olivier Delbosc and Jonathan Levine

Music by Robert Earl Keen

Editing by Josh Noyes

Cinematography by Seamus Tierney

Main Cast:

Spencer Treat Clark … Ethan Elok

Michael Fassbender … Coach James Christian

Amber Heard … Kelsey Elok

Jeremiah Hall … Matthew Madison

Jaquelyn Xavier … Leah Weston

Adam Scott … Roger Elok

Dianne Wiest … Sharon Elok

Tagline: "When it comes to wrestling yourself… the victory seems further from reach.”

Plot: Graduation is just days away and this is his final wrestling meeting with Coach Christian and the boys. They all spend the final day competing in playful matches and Ethan Elok continues to toss and pin his way into pin after pin. Even outside of the competitions, he’s got to remain on top. Ethan is still overcoming the shock of turning eighteen, and his relationships with his best friend Matthew and his gal pal Leah have only spiraled out of control; Matthew finding company with a group of delinquents and Leah no longer interested in the occasional screw. After walking to that podium and accepting that diploma - school no longer a daily activity – Ethan dives into a world of emptiness. Nothing seems to be going on around him, and days spent at home are still as absent from his mother Sharon as they were during schooling hours.

But in this time – these days that pass by slowly – Ethan begins to collect visions involving himself. You can see in his eyes the desperation and the confusion concerning the direction of his life; and you can tell just by the way he speaks to his burnt-out older sister Kelsey that his emotions are slowly draining out of him. Between him and his mother, though, he feels like a reconnection with the deadbeat father he hasn’t seen in over a decade (save for the year’s wrestling competition he just so happened to show up to) may be the key to piecing together a solace to his complicated emotions.

In the wake of this upcoming event (an expensive dinner ultimately arranged by the father himself, Roger – who can’t normally afford such an occasion), Ethan alongside his mother and sister engage in an exhilarating conversation with the man that abandoned them all. All three react in different ways to the family history, but they all wrestle with their feelings while Roger still finds himself incapable of being the better person he wants to be. This moment surely becomes what Ethan was hoping for. Late the night of the dinner, returning home, two separate emotional talks between both sister Kelsey and mother Sharon opens his eyes to what he wants to do with his life. And just like that, he packs his things and walks out of the house, stealing Sharon’s keys on the way. Shadows no longer swallow him, but dance along with him as he passes each streetlight.

Press Section: Upon announcement of the film “Pinhead”, almost nobody felt it would add up to anything other than a sports drama that would be forgotten months after its theatrical release. However, Focus Features wasn’t being dumb when they backed the film up completely and allowed Jonathan Levine to put together a film of such immaculate naturalism and somber beauty. “Pinhead”is a sports drama – and a wonderful one, at that – but it’s not a film about who’s going to win a big competition or how good the protagonist is at the sport. It’s a film in which a boy spends years of his life projecting his frustrations through his physical wrestling skills and, ultimately, forced into finding a solution mentally in order to begin what he is to ultimately become. An adult.

Director Jonathan Levine brilliantly constructs various human themes under auteur allusions to form a tapestry expressing the universal coming-of-age story in a wonderfully magical way. Throughout the film - as the authenticity of the story is told through painful silences and bruising dialogue between characters – director Levine manages to subtly bring together metaphoric parallels between the main character of Ethan and of a superhero. From his name to the blue uniform he wears while wrestling on the mats, the character of Ethan is a frustrated person who fights the negative with his alter-ego (fellow jocks and friends in school have given him the nickname “Pinhead”). Although this isn’t about saving the world as much as his own demons, Levine makes it so that the character is portrayed as a symbolic (and perhaps director-personal) hero for those who can relate.

For the role of Ethan Elok, Levine searched out an actor who was fragile enough to show vulnerability, yet daring enough to bulk up to the challenge of showing Ethan’s aggressive flaws. For the part, Levine chose Spencer Treat Clark, who gives a scorching performance that resonates deeply. Whether it be the way his thoughts are projected through his eyes (after the first act, when his character is no longer in school, his performance mostly consists of an eerie silence in which he must emote through body language to keep the audience’s sympathy) or through the way he creates animalistic pathos during the wrestling sequences that verge on disturbing. It’s a brilliant, breakthrough performance that instantly creates a connection between viewer and character.

The rest of the cast is composed of a variety of terrific and natural actors and actresses who bring great depth to their supporting parts. The film is sternly shown from the eyes of Ethan, giving the supporting performers the task of making characters that only appear every so often in the film fully developed and functional at consistent wavelengths. Perhaps the largest of the supporting players is the role of Coach James Christian - played brilliantly by Michael Fassbender. The kind of stock character that is normally played to overtly hyper levels is given a fairly realistic treatment by Fassbender, who is unafraid of keeping his character’s vulnerability present in his actions even while he projects a fierceness and power over the boys on his team. There are two notably strong moments in Fassbender’s performance that makes him a strong candidate for a Best Supporting Actor nomination.

There’s a scene near the beginning of the film where Coach Christian expresses how much he is proud and respectful toward his players. It’s a monologue that could have easily fallen to melodramatic cheesiness, but Fassbender makes it so that it rubs off as painfully raw and heartbreaking as possible. He doesn’t shed a tear, but you can feel the sincerity in his voice. He really cares. It’s not until later in the film (during the actor’s second standout moment) that this speech takes on a stronger relevance. There’s a simple moment between Ethan and Coach Christian (which occurs at the end of the second act during a flashback to the competition that Ethan’s father showed up to) in which, after Ethan’s uniform rips during a match exposing his genitals to everyone in attendance, the coach chases the boy down to the locker room and embraces the shattered young adult. Levine makes the perfect judgment as director to linger on this shot by focusing on Fassbender’s face, his chin pressed against Ethan’s head as his eyes become viciously glassy as if to share the boy’s embarrassment and humiliation. It’s one of the film’s first moments of pure connection between Ethan and another person.

In a supporting role that goes totally against what has ever come from her before, Amber Heard sheds away all of her sex appeal for a performance that verges on a quiet tour-de-force. With dark brown hair, piercings, and eyes that look to be baked completely from her skull – Heard is a revelation in her role as Ethan’s older sister Kelsey. Heard only has a total of two big scenes in the entire film (as well as several little ones sprinkled here and there), but she sells the hell out of screentime by showcasing her commanding presence and her blissful naturalism. In her first scene, a conversation between her and Ethan on a couch following his graduation (and her return from a rehab center), we get a heartfelt exchange of words in which, while obviously tripping on some kind of drug, Kelsey expresses how she is truly happy for her little brother. “You’re nowhere like me. You’re out there somewhere. You’re not a loser.” This delivery beautifully contradicts what she says during a later moment in the film following the disastrous dinner with their father. Outside the restaurant, Ethan (who in the first scene involving Kelsey expressed his disgust with her smoking habit) begs for a cigarette “just to see if it does what you say it does!” This plea from him makes his sister slightly breakdown, as Heard delivers a scene of pure magnetic ferocity. Obviously holding back from crying hysterically by trying to project strength in her voice – she screams at her brother, letting it all flow out. “You’re dead, just like me, motherfucker. Don’t try to act like you’re not gone, too…” and her rant flows out with hostile rawness before closing up in a beautifully touching moment where they both share a laugh. There’s a serene understanding between Clark and Heard in their performances that makes them feel undoubtedly like siblings. That lifelong relationship – that bond- can be felt.

With Adam Scott and Dianne Wiest, who play the roles of father Roger and mother Sharon, respectively – Levine pulls off a bittersweet void of haunted souls by giving these two performers ample honesty to their roles as they make us believe that they were once an oddball couple (Sharon being decades older than Roger) when they conceived both of their children. It was obviously Roger who called off their romance, and he doesn’t seem to really regret it. He’s quite naïve, like a child, in the climactic dinner scene as he can’t seem to read the signals that Sharon still might have feelings for him. Both Scott and Wiest make this long-lost connection singe through the looks and words they speak to one another. The dinner scene is a master-class of subtly between the two – Scott looking rugged and shaggy in a faux tuxedo that is obviously too big for him, while Wiest lights up with a smile over his lame attempt of looking higher class.

Scott plays humorously with his character, but never makes Roger a caricature. He’s a crappy father and a dishonest person – but there’s a glimmer of love in him that seems to be lurking under the shell. The dinner scene almost feels surreal with Scott’s darkly humorous performance compared to the somberness the rest of the film possesses… but it never feels out-of-place as it slowly escalates to a compelling confrontation between father and son. The fire in Scott’s voice in that argument surprises and sends chills up the spine.

Another fantastically real moment in the film is a scene toward the end of the film involving Sharon showing Ethan a picture of her and his father from back in the day. Levine makes the terrific decision to never show the picture but, instead, has the camera lingering outside of the dining room for one long, uncut five-minute take. The audience peers directly into a very intimate moment between the two from a distance – never interrupting the beautiful moment between the two.

In smaller roles as relationships slipping away, unknown low-budget indie actors Jaquelyn Xavier and Jeremiah Hall bring memorable work to their very small parts. After the first act, they slowly fade from the film – but they perfectly capture the innocence and peculiarities of becoming an adult and realizing their lives may be going in a terrible direction. After having sex with Ethan at a senior party, Leah (Xavier) expresses how much she thinks she’s in love with another man; one who Ethan becomes either jealous or weary of (something else Levine beautifully leaves ambiguous.) There’s a final scene with former best friend and fellow wrestler Matthew (Hall) that blisters with hurt, in which both friends exchange a solemn look at one another. This following their previous scene together in which Matthew “can’t understand you anymore. You used to be a beast. You seem to be losing your claws, man. What’s happening to you?”

Overall, by breathing such liveliness into every character, the ensemble perfects their parts with flesh and blood – all feeling as human as can be. Director Levine amazingly avoids becoming episodic with the film in the way he weaves the many moments together with the use of brilliant film editing that never feels the need to play things out in typical linear motion and cinematography that feels almost French New Wave in its color palettes and use of color for symbolism. For example, the film opens up with the final wrestling meeting as Ethan attacks fellow mates - but the scene is intercut with Ethan in the locker room afterward as he strips from his uniform and takes a shower. Back and forth. We are first introduced to Pinhead – but we are going to get to know the naked truth about Ethan Elok behind that suit.

We experience a first act of the film dedicated to his graduation and the last moments with classmates and friends (Levine makes the wise decision of portraying the senior party in a bland, rather than typical John Hughes-cinematic fashion) and then the second act as we get to understand the true Ethan free of social influence (there’s a wonderful scene where he watches Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru on the television and can’t look away from it) and then leading up to the eventual dinner with the broken family (a nearly fifteen-minute long sequence that slowly boils to fury) that is preluded with the lengthy flashback to the ghostly piece of the Pinhead’s history. It makes sense, then, why Levine decided to end the film on that final shot. After packing up his things and stealing his mother’s car, Ethan drives away as passing shadows cast from the streetlights swipe over his face. The rich colors of his blue wrestling uniform and the bright reds of the gymnasium and locker room are no longer there. Neither are the greys of his mother’s home, or the uncomfortable vomit green of the restaurant. Only a warm and inviting yellow glow. Victorious.

Awards Consideration

Best Picture

Best Director – Jonathan Levine

Best Original Screenplay

Best Actor – Spencer Treat Clark

Best Supporting Actor – Michael Fassbender

Best Supporting Actor – Adam Scott

Best Supporting Actress – Amber Heard

Best Supporting Actress – Dianne Wiest